March 2, 2013

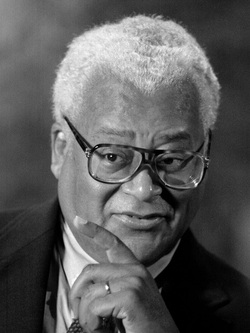

I am more than thrilled that much of the extensive interview I did with

Reverend Lawson back in 2007-08 has finally seen print, in this month’s issue of

The Believer. Here’s the excerpt they put on their web page. I’m waiting for the

hard copy to give to Jim Lawson who may have forgotten by now that he ever

talked to me.

Here's a link to the excerpt The Believer posted at their website.

To read the full piece, if you're not a subscriber, the magazine is available from The McSweeney’s Store.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed